or Searching for the Origins of Elvo-Indo-European in Tolkien’s Elvish Lexicon

|

Also by this author:

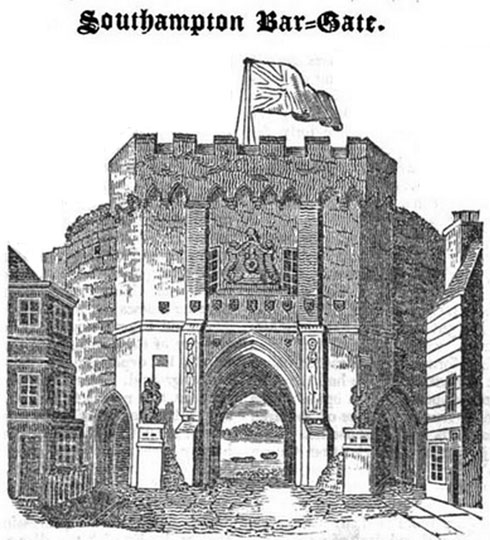

| Read a SampleBarad (fortress)The Noldorin word Barad is glossed as fort | tower | fortress in The Etymologies under the root BARAT–, which is a sparse, penciled entry. (HoMe v.390; VT45.7; S.356) This element is found in a number of place names, such as Barad-dûr (The Dark Tower), Barad Eithel (Tower of the Well), and Barad Nimras (White Horn Tower). (S.318, 319)Christopher observes that his father used “a kind of ‘historical punning’ here and there,” and gives the example of the root SAHA– (be hot), which yields, in addition to saiwa (hot) and sára (fiery), the word Sahóra (the South). [Compare Sahara, the largest hot desert in the world.] In addition, Christopher noted “several resemblances to early English that are obviously not fortuitous, as hôr (old), HERE (rule), rûm (secret [whisper]).” (HoMe i.248) The word barad appears to be another such ‘not fortuitous’ resemblance to English. The gloss of fort | tower | fortress points a comparative linguist to an English word with almost the same sense and consonant silhouette: Baryate > Bargate in Modern English.[1] A particularly famous Bargate is located in Southampton. It is a Grade I listed building.

“The grand and venerable Bar-gate of Southampton is universally admired. … The principal and indeed only approach to Southampton from the land, is by an extensive and well-built suburb. It was formerly separated from the town by a very broad and deep ditch, … which was crossed by an arched bridge leading to the large and extremely beautiful gate called emphatically the Bar. This, it may be observed, was anciently the name of those edifices now called gates; while the word Gate signified the street or road leading to the Bar. At York this ancient phraseology prevails to this day: Mickle-gate leads to Mickle-gate Bar, Walm-gate to Walm-gate bar, and so of the rest.”[2] “The Bar gate was anciently the north gate of the town, and approached from without by a drawbridge across the wide moat that encircled the walls on the land side. … Bar is the old name for the gate itself; Gate—A[nglo]-S[axon] geat—properly signifying the road, access to which was closed by the bar.”[3] Compare the Proto-Germanic *gatwǭ (street, passage), the Swedish gata (street), the Icelandic gata (street, road), the Modern Norwegian gate (a street), the Danish gade (street), and the Finnish katu (street, a loanword from Swedish). In other words, the old element gate carried the sense of a road, and bar carried the sense found in the modern word gate, the place at which the course of the gate (street) was barred.

Parma Eldalamberon XVII gives a parse of √BAR-AT/AD (PE17.22-23, 150), which yields a gloss with a meaning suggestively similar to the sense of Bargate: A bargate was a militarized structure athwart the road that led to a walled city. It provided security for the entrance to the city, and allowed the entrance to be closed. This is very similar in meaning to the gloss Tolkien provided for barad: fort | tower | fortress, as can be seen clearly in the illustration of the Bargate to Southampton above, which has definite characteristics of a tower fortification. The silhouette of the English word bar-gate has been cleverly modified to turn it into a word with Elvish morphology, by applying lenition to the second element (gate). Bar (security barrier) + gate (street) L> at(e) Notes: [1]English Place-name Society: Survey of English Place-names, volume 58, Cambridge: The University Press, 1985, pp. 9, 13. [2]The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, volume 3, No. LXXII, Saturday, February 28, London: J. Limbird, 1824, p. 137. [3] Richard John King, A Handbook for Travellers in Surrey, Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight, second edition, revised and enlarged, London: John Murray, 1865, pp. 261-262.

|

Pagination: xliv + 256. Trade Paper $14.95.

To learn more about the book, follow the links below.